Definition of Memoization

The term "memoization" was introduced by Donald Michie in the year 1968. It's based on the Latin word memorandum, meaning "to be remembered". It's not a misspelling of the word memorization, though in a way it has something in common. Memoisation is a technique used in computing to speed up programs. This is accomplished by memorizing the calculation results of processed input such as the results of function calls. If the same input or a function call with the same parameters is used, the previously stored results can be used again and unnecessary calculation are avoided. In many cases a simple array is used for storing the results, but lots of other structures can be used as well, such as associative arrays, called hashes in Perl or dictionaries in Python.

Memoization can be explicitly programmed by the programmer, but some programming languages like Python provide mechanisms to automatically memoize functions.

Memoization with Function Decorators

You may consult our chapter on decorators as well. Especially, if you may have problems in understanding our reasoning.

In our previous chapter about recursive functions, we worked out an iterative and a recursive version to calculate the Fibonacci numbers. We have shown that a direct implementation of the mathematical definition into a recursive function like the following has an exponential runtime behaviour:

def fib(n):if n == 0:return 0elif n == 1:else:return 1return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

We also presented a way to improve the runtime behaviour of the recursive version by adding a dictionary to memorize previously calculated values of the function. This is an example of explicitly using the technique of memoization, but we didn't call it like this. The disadvantage of this method is that the clarity and the beauty of the original recursive implementation is lost.

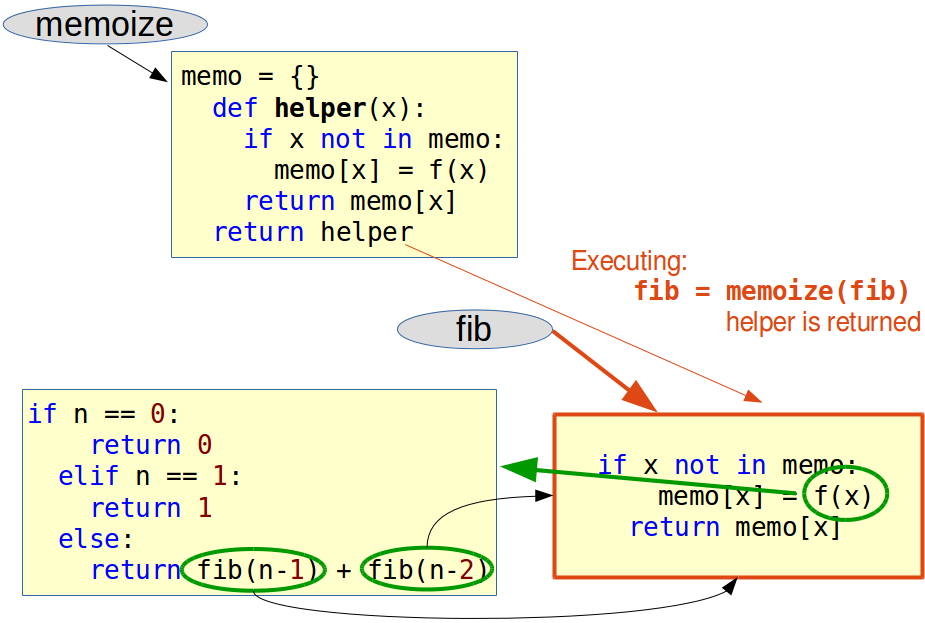

The "problem" is that we changed the code of the recursive fib function. The following code doesn't change our fib function, so that its clarity and legibility isn't touched. To this purpose, we define and use a function which we call memoize. memoize() takes a function as an argument. The function memoize uses a dictionary "memo" to store the function results. Though the variable "memo" as well as the function "f" are local to memoize, they are captured by a closure through the helper function which is returned as a reference by memoize(). So, the call memoize(fib) returns a reference to the helper() which is doing what fib() would do on its own plus a wrapper which saves the calculated results. For an integer 'n' fib(n) will only be called, if n is not in the memo dictionary. If it is in it, we can output memo[n] as the result of fib(n).

def memoize(f):memo = {}def helper(x):if x not in memo:memo[x] = f(x)return helperreturn memo[x] def fib(n):return 1if n == 0: return 0 elif n == 1:fib = memoize(fib)else: return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)print(fib(40))

Let's look at the line in our code where we call memoize with fib as the argument:

fib = memoize(fib)

Doing this, we turn memoize into a decorator. One says that the fib function is decorated by the memoize() function.

We will illustrate with the following diagrams how the decoration is accomplished. The first diagram illustrates the state before the decoration, i.e. before we call

fib = memoize(fib). We can see the function names referencing their bodies:

After having executed

fib = memoize(fib) fib points to the body of the helper function, which had been returned by memoize. We can also perceive that the code of the original fib function can from now on only be reached via the "f" function of the helper function. There is no other way anymore to call the original fib directly, i.e. there is no other reference to it. The decorated Fibonacci function is called in the return statement return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2), this means the code of the helper function which had been returned by memoize:

Another point in the context of decorators deserves special mention: We don't usually write a decorator for just one use case or function. We rather use it multiple times for different functions. So we could imagine having further functions func1, func2, func3 and so on, which consume also a lot of time. Therefore, it makes sense to decorate each one with our decorator function "memoize":

fib = memoize(fib)func1 = memoize(func1)func2 = memoize(func2)# and so onfunc3 = memoize(func3)

We haven't used the Pythonic way of writing a decorator. Instead of writing the statement

fib = memoize(fib)

we should have "decorated" our fib function with:

@memoize

But this line has to be directly in front of the decorated function, in our example fib(). The complete example in a Pythonic way looks like this now:

def memoize(f):memo = {}def helper(x):if x not in memo:memo[x] = f(x)return helperreturn memo[x] @memoize def fib(n):return 1if n == 0: return 0 elif n == 1: else:print(fib(40))return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

Using a Callable Class for Memoization

This subchapter can be skipped without problems by those who don't know about object orientation so far.

We can encapsulate the caching of the results in a class as well, as you can see in the following example:

class Memoize:def __init__(self, fn):self.fn = fndef __call__(self, *args):self.memo = {}self.memo[args] = self.fn(*args)if args not in self.memo:if n == 0:return self.memo[args] @Memoize def fib(n):return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)return 0 elif n == 1: return 1else:

As we are using a dictionary, we can't use mutable arguments, i.e. the arguments have to be immutable.

Exercise

Our exercise is an old riddle, going back to 1612. The French Jesuit Claude-Gaspar Bachet phrased it. We have to weigh quantities (e.g. sugar or flour) from 1 to 40 pounds. What is the least number of weights that can be used on a balance scale to way any of these quantities.The first idea might be to use weights of 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 pounds. This is a minimal number, if we restrict ourself to put weights on one side and the stuff, e.g. the sugar, on the other side. But it is possible to put weights on both pans of the scale. Now, we need only four weights, i.e. 1, 3, 9, 27Write a Python function weigh(), which calculates the weights needed and their distribution on the pans to weigh any amount from 1 to 40.

Our exercise is an old riddle, going back to 1612. The French Jesuit Claude-Gaspar Bachet phrased it. We have to weigh quantities (e.g. sugar or flour) from 1 to 40 pounds. What is the least number of weights that can be used on a balance scale to way any of these quantities.The first idea might be to use weights of 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 pounds. This is a minimal number, if we restrict ourself to put weights on one side and the stuff, e.g. the sugar, on the other side. But it is possible to put weights on both pans of the scale. Now, we need only four weights, i.e. 1, 3, 9, 27Write a Python function weigh(), which calculates the weights needed and their distribution on the pans to weigh any amount from 1 to 40.

Solution

-

def factors_set():factors_set = ( (i, j, k, l) for i in [-1, 0, 1]for j in [-1, 0, 1]for l in [-1, 0, 1])for k in [-1, 0, 1] for factor in factors_set:if n not in results:yield factor def memoize(f): results = {} def helper(n):def linear_combination(n):results[n] = f(n) return results[n] return helper @memoizeweighs = (1,3,9,27)""" returns the tuple (i,j,k,l) satisfying n = i*1 + j*3 + k*9 + l*27 """if sum == n:for factors in factors_set(): sum = 0 for i in range(len(factors)): sum += factors[i] * weighs[i]return factorsWith this, it is easy to write our function weigh().def weigh(pounds):weights = (1, 3, 9, 27)scalars = linear_combination(pounds)left = "" right = ""if scalars[i] == -1:for i in range(len(scalars)):elif scalars[i] == 1:left += str(weights[i]) + " "for i in [2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 20, 40]:right += str(weights[i]) + " " return (left,right) pans = weigh(i)print("Right pan: " + pans[1] + "\n")print("Left pan: " + str(i) + " plus " + pans[0])

No comments:

Post a Comment